Are Snuff Films Real?

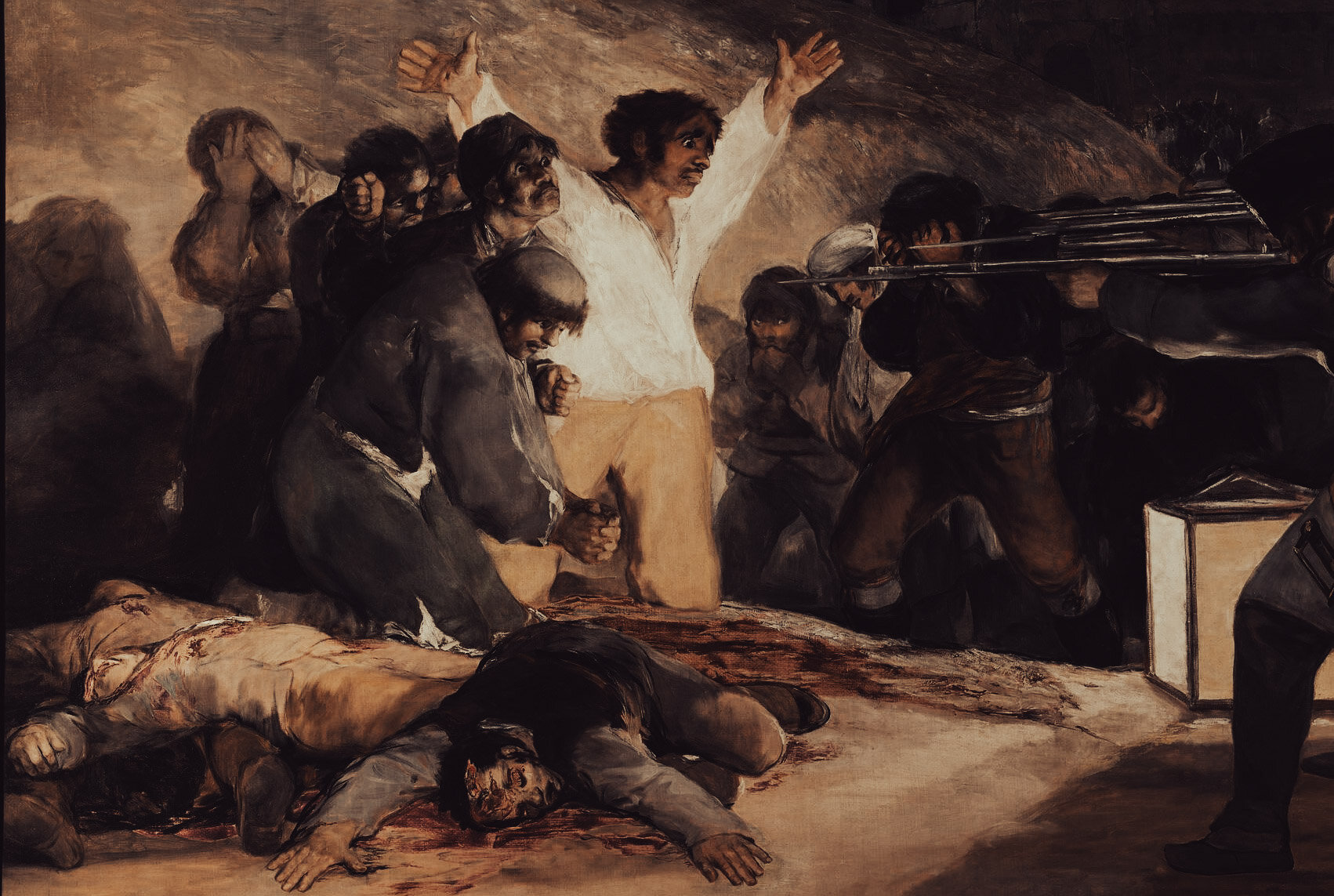

Snuff: Making fake violence look real

The exploitation film Cannibal Holocaust (1980) featured an incredibly realistic impalement scene. The actress who played it seemed to have disappeared and eventually, the director Ruggero Deodato had to testify in court that his actors were all alive.

Maybe it was Deodato himself who spread the rumor, just like the distributor of Snuff (Findlay and Fredriksson, 1976), who paid “feminists” to picket movie theaters to protest the film’s misogynistic content. A publicity stunt, nothing more nothing less. A lot of horror films are built on the premise that the content you’re watching is “real footage” of disturbing events, found somewhere by researchers, fanatics, or film crews. We all know it’s fake.

Still, filmmakers rack their brains trying to make a fake display of violence look so realistic that people would buy that premise and believe that they’re watching someone who has really been tortured and killed. Single shot, frontal static camera, no chances to cut and edit, no room for special effects, put everything visibly on display, and there you have it – a “snuff” film, namely a film (staged and produced) featuring real violence and death, made for entertainment and profit. Or a film that is so craftily made that everyone would believe it’s snuff. Or is that exactly what snuff is?

To this day, there is no record of “real” snuff footage.

There are only a few alleged cases, such as the murder clips that the Dnepopretovsk maniacs claimed to have made for profit in 2007 (a claim that has never been verified).

The myth of “snuff” films and its appeal

The myth of footage of people being tortured and killed circulating somewhere is powerful. The reaction to extreme graphic violence “no, this cannot be real” is complementary to the suspicion that real snuff footage could sneak in, perfectly camouflaged among faux-snuff films doing their best to look real.

In Alejandro Amenàbar’s Tesis (1996), a film about snuff films, Angela is researching violence in the media. She watches a lot of extreme content for academic purposes, but it’s only when her supervisor dies from a heart attack from watching a violent video borrowed from the library that she realises that someone in her university is actually making snuff films. “Real” snuff films, if properly disguised, may be hard to find.

[In Amenàbar’s Tesis, Angela researches violence, but isn’t as objective and detached as she thought she would be. She grows increasingly fascinated by the topic and sexually attracted to the snuff filmmaker Bosco]

[Blinded by her fascination, she ends up in Bosco’s snuff set]

If real snuff films existed, they wouldn’t be very interesting from an artistic point of view. There is hardly any narrative in a film where someone is tortured and murdered. Snuff films only purport to “show,” as in the “cinéma vérité” tradition where the filmmaker wants to be nothing more than a fly on the wall.

In this sense, snuff is somewhat similar to porn or reality television. In all of these cases, the acting is minimal compared to regular films, but there is a mise-en-scène, and the film is recorded and replayed for others to watch. Professor and film critic Eric Cazdyn talks about a “reality culture” characterised by constant thirst for footage: surveillance cameras, youtube videos, amateur porn.

We just love to look at reality – on a screen.

You could say there is a difference, since snuff actors die on camera. As we said, real snuff is an urban legend. It wouldn’t be smart of criminals to provide such precious evidence of their acts. And if someone did it anyway, you’d probably hear about it in the news instead of seeing it in a film.

Snuff films as copies without original

The Age of Simulation

It may sound quite intricate to say that fake snuff is the only real snuff we have, while alleged real snuff is a myth. Why make something imitating a reality that doesn’t exist?French philosopher Jean Baudrillard thought that this kind of construction was ubiquitous in our era – often called the “postmodern” era, from the 80s onwards.

He called it a “simulacrum,” a copy without original, something fake that “desires” to be real and offers itself as reality, in reality’s place.

In his famous 1981 book Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard describes our age as an “age of simulation” in which the reality we perceive is largely replaced by these copies lacking any original referent. There is a temporal transition. Initially, the real is simply imitated (say, the portrait of a person). Then, as the copy resembles the real in an increasingly sophisticated way (think of a photograph), the difference between the two starts to disappear. Let’s take Baudrillard’s example. To preserve the delicate Lascaux caves, curators decided to build a perfect replica, accessible to tourists, so that they could experience the caves without damaging them. Does it even matter that tourists actually looked at a copy? Not according to Baudrillard:

“It is possible that the memory of the original caves is itself stamped in the minds of future generations, but from now on there is no longer any difference: the duplication suffices to render both artificial.”

When copies substitute reality

In what Baudrillard calls the age of simulation, the real is no longer just copied, but entirely substituted by its copy – the real was never even there. Disneyland, virtual reality, opinion polls, computers,... all of these things have no prototype in the real world but are nevertheless extremely real in our lives. These false copies, the simulacra, are perfectly adherent to patterns of reality, rather than to reality itself: they imitate models or matrices of the real, but not the real itself.

Snuff films - the only existing ones, the simulacra - are just as fake as any other film that imitates reality, more so than porn or reality TV, which still have an element of reality to them. But what they imitate is not reality, because real snuff doesn’t exist. They imitate patterns of reality – as Baudrillard would say, models and matrices of the real. Snuff imitates what the reality of someone being tortured and murdered would look like, but the original referent was never there: nobody died on camera.