John Carpenter’s Ideology Sunglasses

Hands down the coolest film ever made about ideology is 'They Live'. It’s got an incredibly catchy musical theme, wrestler Roddy Piper playing the main role, and a bunch of cheesy quotes such as “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass – and I’m all out of bubblegum.” With a small budget and a lot of imagination, it tackles some of the most complex political issues we face in our daily lives: propaganda, exploitation, false consciousness, and power. But does it tackle them well?

They live, we sleep

Roddy Piper, credited in the film as “Nada” (nothing, the universal subject), is a drifter who comes to Los Angeles in search of a job. He settles in a shantytown with a man he befriends, construction worker Frank. Pretty soon, he starts to realise that some folks in the shantytown are involved in suspicious activities and regularly meet in a nearby church. After the police brutally raid the church one night, Nada decides to go take a look. A strange writing on the wall says “They live, we sleep.” But he is disappointed when, instead of explosives and subversive material, he just finds a box of sunglasses.

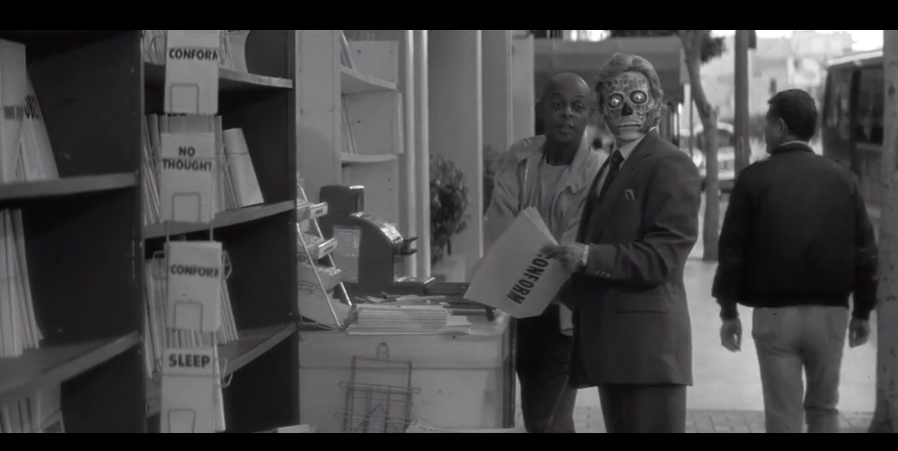

Walking around the streets of LA, Nada decides to put on the sunglasses – they give him black and white vision and a headache. But he also sees the world differently. He looks at advertisements, he sees “Obey.” He flips through magazines in a shop and reads “Do not question authority” and “Consume.” Dollars read “This is your God.” Nada is seeing through the deception, right into the real message of everything.

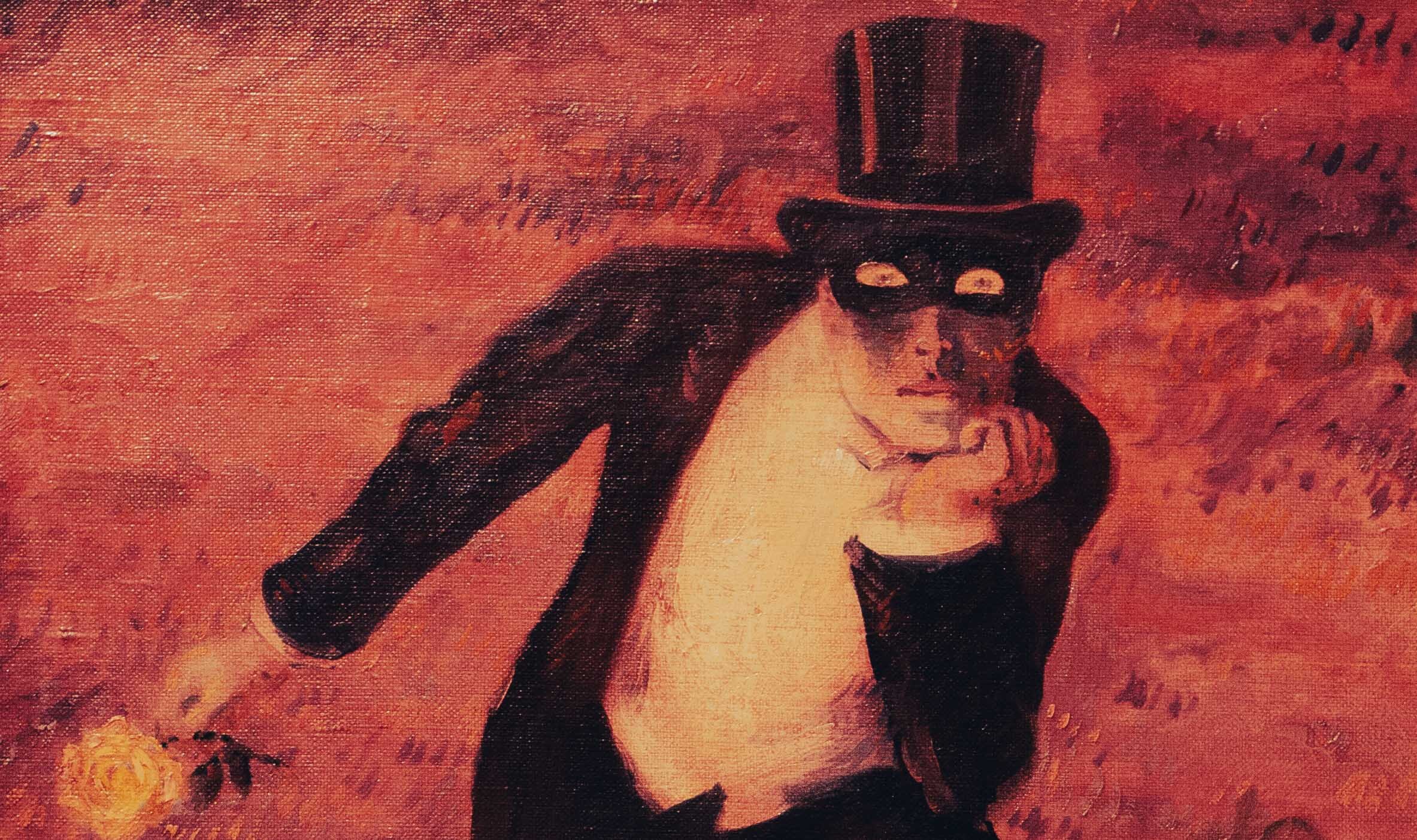

When he turns to a man wearing a suit and an expensive watch, Nada sees a disgusting rotten face. That is who “they” are: the upper class turned into an ugly alien race. They live parasitically out of us, and we, their livestock and the source of their money, we sleep, fed by their subliminal messages.

Nada is shocked and immediately wants his friend Frank to put on a pair of sunglasses too. He has to see. Surprisingly for Nada, Frank is very adamant about not putting the glasses on. He has a family to take care of, he cannot afford knowing the painful truth. It takes a surreal fight scene of several minutes for Nada to force the sunglasses onto Frank’s face and, honestly, you feel a bit bad for Frank: all he really wants is to live peacefully with his illusions.

From that moment, Nada and Frank have no other choice but to get into action. They join an underground resistance group made up of people who tried the sunglasses on. After a good deal of shooting and yelling, they manage to infiltrate the coven, where alien yuppies meet to organise their propaganda and then transmit it from an antenna. Shutting down the transmission system means getting rid of the propaganda and unmasking the alien parasites: to show everyone their real appearances.

What Carpenter got right about ideology

John Carpenter himself described They live as “partially a political statement” but mostly “just an action film.” He’s a filmmaker, so he takes a few artistic liberties that make his depiction of ideology allegorical and at times not very accurate. Still, as an artist, he does a great job at conveying a strong message in a symbolic way.

There are a few features of Carpenter’s representation of ideology that are particularly interesting. Let’s take the sunglasses. One might be tempted to imagine ideology as glasses we’re unconsciously wearing and the process of emancipation as the act of putting them off. Carpenter’s brilliant idea, instead, is precisely to internalise ideology in our regular vision. He shows that ideology penetrates into us so well that we naturally see through it. It is so ingrained in us that we need an external tool to restore our vision.

Ideology, which could be defined very broadly as a world view, is inextricably part of our cognition. There is no thinking outside of ideologies, because we always position ourselves in articulate sets of concepts, beliefs, and values – so in a way John Carpenter is clever in showing that ideology is within us, not without.

Another interesting element in They Live is the difficulties that Nada encounters in convincing Frank to try the glasses on. Let’s take the fight scene - a legendary scene both for the length and craftiness of the fight itself and for featuring another one of Nada’s most memorable quotes: “Either put on these glasses or start eating that trash can.” In the scene, Nada and Frank are in a backstreet and Frank is trying to walk away. Nada goes, “Try these on,” handing the sunglasses to his friend. Frank is defensive, he raises his hands, “Look, you crazy mother…” “Put them on!” says Nada, and Frank tries to escape, “Hey, stay away from me!” Why doesn’t Frank want to put on the glasses? Why is he willing to be beaten up by a big guy like Nada till he’s lying on the floor and bleeding just to make this point? The answer is, because the truth hurts. Frank knows Nada has found out something very unpleasant. A construction worker living in a shanty town, Frank may have very little to lose, and yet he is too afraid to face the truth. He just wants to lead a decent life with his family. He knows that putting the glasses on is a point of no return: once you see the truth, you cannot go back to your normal life.

Liberation is difficult. Since ideology is so pervasive in our lives, we can live comfortably within it. For a person who’s been raised thinking that the ultimate goal in life is to be wealthy, money may be the fastest track to fulfillment, even if it’s difficult to make it. In Marxism and critical theory, this condition of self-deception is called “false consciousness.” Put simply: I think I know what I want, but I am actually making myself miserable. Struggling to get a job in a hyper-competitive labour market, where competition is unfair, based on corruption and socio-economic inequalities – how could that make anyone happy? Yet most of us struggle and would rather do so than admit to ourselves that the world is an intrinsically unfair place.

What Carpenter got wrong about ideology

The glasses and the fighting are great symbolic devices to represent ideology, but Carpenter’s account has its limits. First of all, think about the fact that the exploiters, who fabricate ideology and feed it to the exploited, are aliens. If the upper class were aliens, we wouldn’t feel too bad about wiping them out. Sadly, they are humans too. We may even put on glasses (figuratively speaking) that allow us to see through propaganda: we would still find that the exploiters aren’t easily identifiable.

The alien race device is functional to They Live as it creates a framework of good vs evil which is typical of action films. However, it also creates an overly conspiratorial narrative - no wonder They Live has been criticised for allegedly talking about the Illuminati or even the Jews ruling the world. The alien conspiracy element somehow weakens Carpenter’s depiction of ideology: it flattens its complexity.

According to Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, one of the most important people to have ever reflected on ideology, ideologies are resilient and able to withstand the pressure from competing ideologies. Different ideologies emerging from different strata of society or different cultures always merge and produce particular, at times weird and incoherent results. As religion, for instance, interacts with politics, it can create a mutually beneficial mix and the rise of a new, hybrid, ideology such as conservatism or liberation theology. Christian values of compassion and solidarity can make people who embrace them thus see capitalism as beneficial or as ruthless. The idea of a covert alien conspiracy contradicts the fact that ideologies are in fact open, ever changing and adapting to new circumstances, and continuously negotiated with other ideologies.

Perhaps the most serious thing that Carpenter gets wrong in They Live is the final unplugging. In the film, shooting at the transmitter with a gun is enough to reveal the whole alien conspiracy: people finally see aliens in their real appearances, and all ads, magazines, products, and dollars say “consume”, “submit”, “conform”, and “stay asleep”. The truth comes to the surface. Forcing Frank to see the truth may have been difficult for Nada, but freeing the masses doesn’t seem to be that big of a deal.

Obviously, like most films, They Live builds towards a final resolution, so the destruction of the alien transmitter is a necessary narrative element in order to leave the watcher with the feeling that everything will be alright and that the bad aliens have been defeated. The underlying assumption, however, is that, once an ideology is “removed,” the world becomes neutral again. As if you could perceive reality without a framework of assumptions, conventional beliefs, and values.

Returning to Gramsci, he thought that ideologies differ in the degree to which they are just, liberating, and better for humanity as a whole. Fighting an ideology that isn’t just, liberating, and better for humanity as a whole can only happen by opposing a different ideology to it. But the naive expectation that the world can be seen neutrally has to be given up. This is lacking in Carpenter’s representation of ideology: there is no positive counter-project, no ideological alternative other than an anti-alien sentiment common to all those who’ve had the glasses on.

They Live is quite a unique film: it treats a subject matter that is often ignored by mainstream cinema, but it does so through popular Hollywood film features - action, pulp, happy ending. It is at the same time funny, entertaining, and clever. The black-and-white images of ads saying “Obey'' have entered popular culture - think of the appropriation by Obey clothing, which incorporates fashion and activism. Probably, the film has contributed to making viewers more aware of how sneaky propaganda can be and how scary it is to think that everything we see and consume has been made for us, to deceive us.

Carpenter’s idea was to make a statement against Reaganomics – the political economy of the 80s and 90s and the dominant hegemony to this day. Reaganomics was characterised by unconstrained capitalism and by a system of politics, media, and advertisements that sustained it by promoting consumerism and raising money to a collective obsession. He wanted to show that the messages we encounter in our daily lives aren’t neutral and that ordinary people are fed with fabricated lies so that the system can keep going, to the advantage of the few. He manages to convey this message. Even though his representation of ideology has its limits, They Live remains one the most educational action films ever made.