Doctor Atomic and the scientist’s concern over politics –Part 1

Opera’s id:

Composer: John Adams

Libretto: Peter Sellars

Language: English

Premiere: San Francisco Opera, 2005

The setting of the opera

Los Alamos, New Mexico. June 1945.

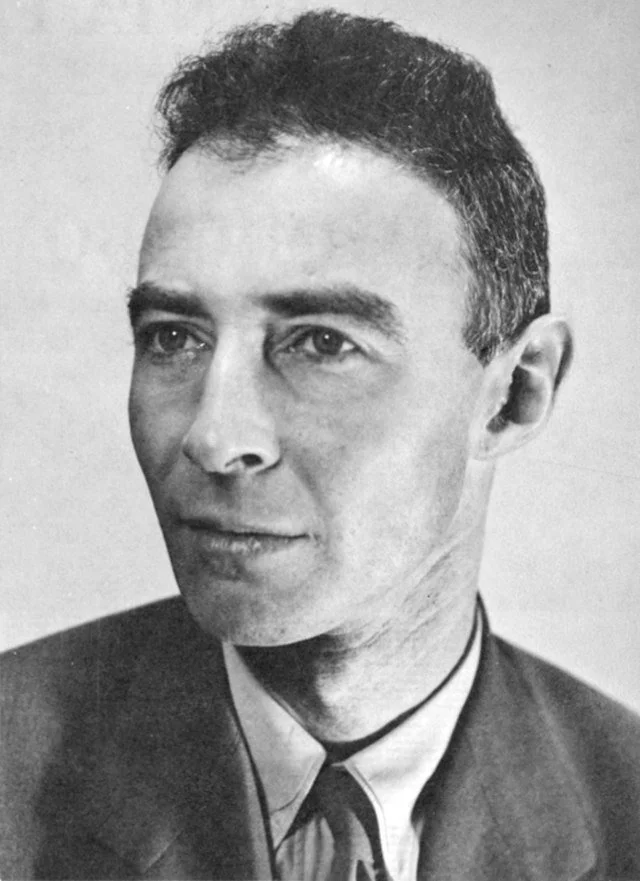

In June 1945, Germany is defeated, but the Second World War has not yet reached its end. Japan is refusing to surrender to the terms of peace proposed by the Allied forces and the war is still raging on the Pacific front. At the same time, unbeknownst to the majority of the world’s population, a top secret project under the code name “The Manhattan Project” is taking place at the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico. A group made up of some of the most talented scientists of the time, under the guidance of the young physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, has been tirelessly working to develop the weapon that would mark the end of the war: the atomic bomb.

This is the setting of John Adams’ contemporary opera Doctor Atomic. Doctor Atomic focuses on the final days before the testing of the bomb, exploring the events that took place and the ethical questions that arose. Most of its characters – J. Robert Oppenheimer, his wife Kitty Oppenheimer, the scientists Edward Teller and Robert Wilson, the military commander General Leslie Groves, the meteorologist Frank Hubbard and the army doctor Captain Nolan – are real-life persons participating in the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. Other characters – the Oppenheimers’ maid Pasqualita and the anonymous members of the chorus (scientists, members of the army, and Tewa Indians, the indigenous inhabitants of Los Alamos) – are people that would have been found in the area. Their history is interconnected in various ways with the creation of the atomic bomb. Moreover, the opera’s libretto is a collage of different pre-existing pieces: it ranges from manuals on nuclear physics to memoirs of the main characters and interview recordings, and from declassified government documents to poems recited by the cultivated Oppenheimers.

The opera is treating the ambivalent role of science as a force of creation and destruction. It evokes questions about whether the use of the atomic bomb can be morally justifiable. However, today is hard to miss its resonance in a broader set of questions around the political role of scientists. We are living in a world where political decisions are often justified as being based on the advice of scientists who are, in turn, called to take a public stance in support of these decisions. Listeners today are probably streaming the opera at home, since lockdowns are being imposed and opera houses are closed throughout the world on the basis of political decisions informed by scientific health committees. Experiencing all this in our everyday lives, it’s almost impossible not to view Doctor Atomic through this broader lens. Keeping in mind that the goal of Adams in this opera was to explore characters rather than re-enact the historical facts, we can explore the moral dilemmas that are raised and the different reactions of its characters to these dilemmas.

Starting the atomic age with clean hands?

The question of the political role of the scientists is at the heart of the first scene of Doctor Atomic. The scientists at Los Alamos, who have been tirelessly working for years on the creation of the atomic bomb, are now confronted with the very real possibility of its use. The different ways in which they react to this possibility demonstrate different ways of understanding the role of the scientist in a decisive moment, when their scientific input is essential for political action but their personal views are not taken into account. In a way, the events that take place in the first scene determine not only the course of the opera, but also the meaning of the characters’ further actions.

The opera begins with a chorus of scientists and army members working at Los Alamos, who announce, in a mix of excitement and fear, that they have been working on a groundbreaking project:

“A weapon has been developed

that is potentially destructive

beyond the wildest nightmares

of the imagination”

This weapon, as they acknowledge, is ideal for unannounced attacks in the war, able to destroy whole cities in a single night. But most unsettling is the end of the chorus:

“This weapon has been created

not by the devilish inspiration

of some warped genius

but by the arduous labor

of thousands of normal men and women

working for the safety of their country”

This line serves as a transition to a discussion between Oppenheimer, the head of the Manhattan Project, and another scientist, Edward Teller (ironically, later known as “the father of the hydrogen bomb”). Teller informs Oppenheimer of a letter he received from another prominent physicist, Leo Szilard. The letter parallels the responsibility of individual Germans for not protesting against the Nazis’ crimes with the responsibility of the American scientists working on the creation of the atomic bomb. Since the people of the United States are unaware of the project for the creation of the bomb, Teller suggests, it is the unique responsibility of the scientists to prevent its unnecessary use, despite the political displeasure that this public stance may cause.

“We scientists,

working on 'atomic power',

are in a position

to raise our voices

without such risks,

even though we might incur

the displeasure of those who

are at present in charge.”

Oppenheimer’s view of the scientists’ role is completely different. He rejects such a public stance as improper and suspect of ulterior motives, insisting that these decisions are for politicians, not for scientists:

“I think it improper

for a scientist

to use his prestige

as a platform

for political pronouncements.

The nation's fate

should be left in the hands

of the best men in Washington.

They have the information which

we do not possess.

Men like Marshall,

a man of great humanity and intellect--

it is for them to decide, not us.”

At this point, Teller is joined by another scientist, Robert Wilson, who wants to alert scientists to the potential implications of using the bomb. Wilson counters Oppenheimer’s argument:

“These questions are not technical questions,

but political and social questions,

and the answers given to them

may affect all mankind for generations.

In thinking about them

the men on the project

have been thinking as citizens

of the United States

vitally interested in the welfare

of the human race.”

Oppenheimer’s view of the scientists’ role is completely different. He rejects such a public stance as improper and suspect of ulterior motives, insisting that these decisions are for politicians, not for scientists:

“I think it improper

for a scientist

to use his prestige

as a platform

for political pronouncements.

The nation's fate

should be left in the hands

of the best men in Washington.

They have the information which

we do not possess.

Men like Marshall,

a man of great humanity and intellect--

it is for them to decide, not us.”

At this point, Teller is joined by another scientist, Robert Wilson, who wants to alert scientists to the potential implications of using the bomb. Wilson counters Oppenheimer’s argument:

“These questions are not technical questions,

but political and social questions,

and the answers given to them

may affect all mankind for generations.

In thinking about them

the men on the project

have been thinking as citizens

of the United States

vitally interested in the welfare

of the human race.”

Wilson wants to circulate a petition addressed to the President of the United States, Harry S. Truman. There, the scientists of the Manhattan Project would state that the creation of the atomic bomb has been justified only through the fears that Germany may have been developing similar weaponry. With the defeat of Germany the attack is no longer justified, at least without giving Japan “a chance to surrender.”

Instead of using the bomb, Wilson argues for a demonstration in the desert, during which representatives of Japan would be able to see its destructive effects. Frustrated with the frantic workings for the creation of the bomb, he laments not having the opportunity to pause for a moment and consider the implications of what is going on.

Oppenheimer does not yield. He lets everyone know that the “upper crust” in Washington have already selected the targets of the forthcoming attacks, and the test of the bomb must go on as planned. Teller appears exasperated:

“You used your scientific stature

to give political advice

in favor of immediate bombing?”

Oppenheimer, however, suggests that he only gave scientific information on the workings of the bomb:

“I explained that the visual effect

of an atomic bombing would be tremendous (…)

The neutron effect of the explosion

would be dangerous to life

for a radius of at least

two-thirds of a mile, a brilliant luminescence.”

According to Oppenheimer, the targets have been selected on scientific criteria as well. What mattered was the estimated psychological impact of the attacks. It has been determined that, to make “a profound psychological impression” on the Japanese, the attacks should take place with no warning. While the chorus of the scientists reads the petition, which underlines the risk of “opening the door to an era of devastation on an unimaginable scale,” Oppenheimer dismisses the possibility of the petition ever reaching President Truman. The scene culminates in Oppenheimer’s announcement that he has already informed Washington of the possibility of several strikes, and Teller’s fearful question:

“Could we have started the atomic age

with clean hands?”

The question remains open to be answered by each member of the audience. Still, it presupposes that in shaping the future of our societies, not only the scientific discoveries, but also the public stance of the scientists play a role. This implies the scientists’ responsibility for this future. Through the scene, we can view Oppenheimer, Wilson, and Teller as representatives of three exemplary models of action.

Three competing models of action

Oppenheimer adopts what could be described as a technocratic view. Technocrats assume that political decisions should be made by experts, who have all the necessary knowledge to make good decisions. Political problems have a right and a wrong answer; and it is a matter of technical knowledge to find this answer. Oppenheimer is a scientist and, as such, he does not consider himself to be the right person to decide on the use of the atomic bomb. These decisions – political decisions – should be made, in his view, by men “of great humanity and intellect.” In Oppenheimer’s view, these are the politicians, who are better equipped for this job and, additionally, hold information not available to others.

It’s not that Oppenheimer is indifferent to what is going on in society. After all, he is the leader of the Manhattan Project. But he believes that scientists should restrict themselves to providing the government with all the necessary information that is related to their field. Collecting information from various different fields (technical information about the bomb from Oppenheimer, information about the estimated impact of using the bomb from psychologists, etc.), the government will be able to determine the best course of action in ways inaccessible to the broader public.

This view on the political role of the scientist is challenged by Wilson. Wilson’s opposition to Oppenheimer’s view is twofold. One the one hand, he insists that the questions related to the use of the atomic bomb “are not technical questions, but political and social questions” that will have broad, tangible consequences for people’s lives for generations. This undermines Oppenheimer’s claim that the decisions of the government are technical, merely implementing the information received from experts in various fields. Instead, the decisions taken emerge as political decisions, related primarily to the government’s judgment and evaluation of the ongoing circumstances. After all, knowledge that the bomb is an effective weapon does not entail that this weapon should be used.

On the other hand, the fact that these questions are “political and social questions” means that not only governments, but also every citizen can – and should – form an opinion over them and publicly defend it. The problem with the Manhattan Project is that, while it affects the whole of humanity, only few scientists and government officials are aware of its existence. In this case, it becomes imperative for the scientists who disagree with the use of the bomb to react and try to deter the government. For Wilson, in doing so, the scientists at Los Alamos have not been acting “improperly,” going beyond their role. On the contrary, they “have been thinking as citizens of the United States, vitally interested in the welfare of the human race.”

In between these two opposed understandings of the political role of the scientist stands Teller. Having received a letter calling him to action against the use of the bomb, Teller is torn on how to react. In his very first lines, he clarifies to Oppenheimer that he has no hope of clearing his conscience. The creation of the atomic bomb is “so terrible that no amount of protesting or fiddling with politics will save our souls.” Later on, he refers to himself as “trapped” by the “machinery” of the bomb. However, his approach is much more individualized than Wilson’s. He appears to agree that the decision on the use of the bomb is a political decision, but does not consider collective action as a way of dealing with it. His only hope is that the tremendous effects of the bomb will deter everybody from using it again in the future, conceding that the actual use of the bomb may be the best way to achieve this. This brings him much closer to Oppenheimer than to Wilson at the end of the scene: while Wilson, accompanied by the chorus, stands for widespread mobilizations against the bomb, Teller cynically asserts that “the more decisive a weapon is, the more surely it will be used, and no agreements will help.” While not being blind to the political implications of his actions as a scientist, by rejecting the possibility of impactful public mobilization Teller is trapped in the role of the spectator. He is merely watching what is happening, hoping for the best result.

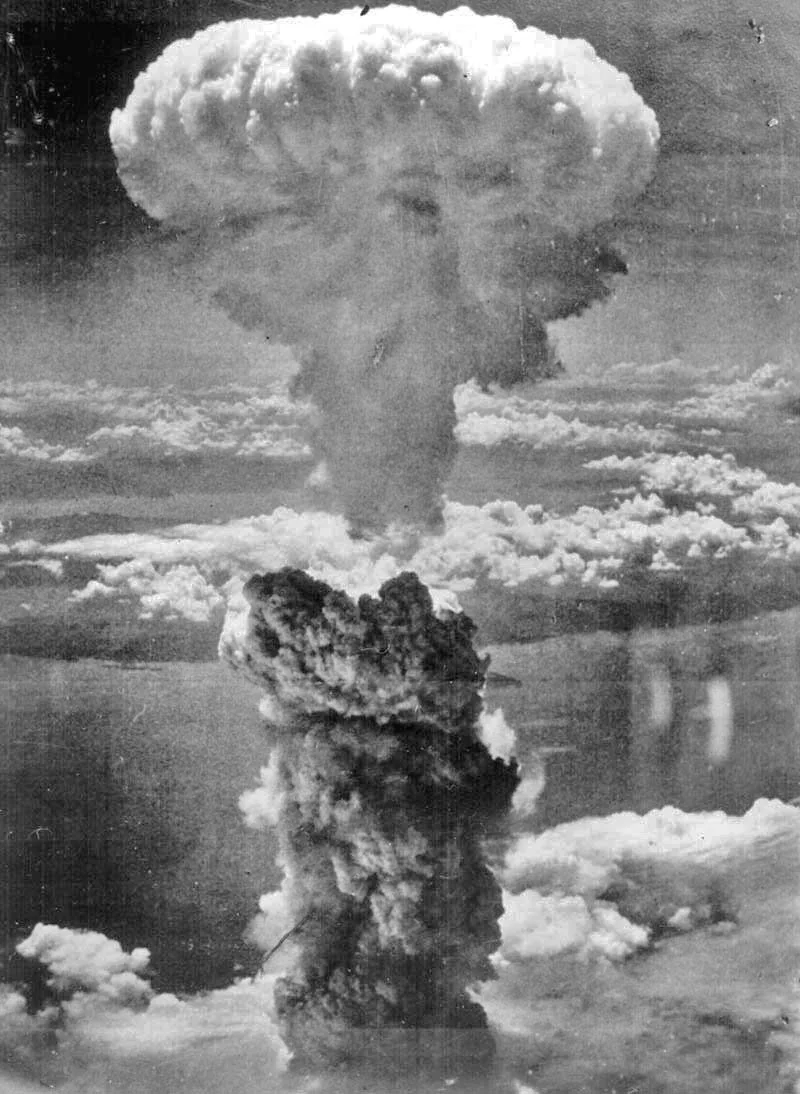

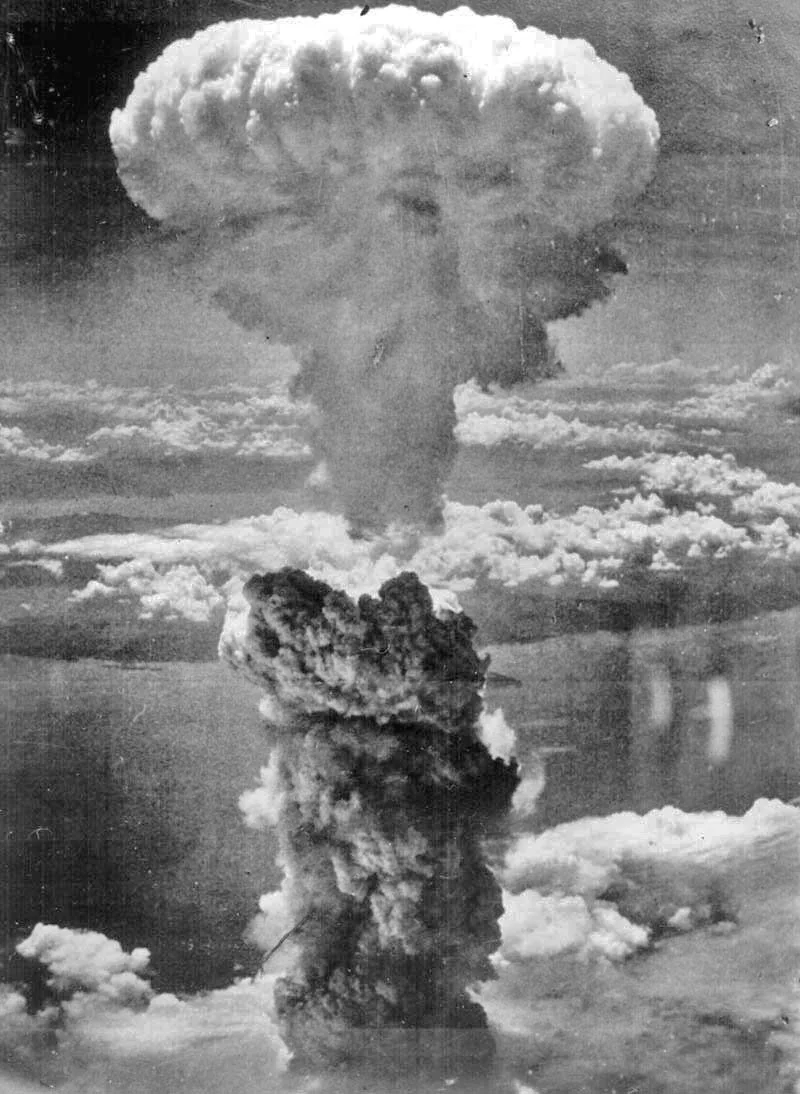

The audience of the opera today knows that, ultimately, after its successful testing at Los Alamos, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, followed by a second bomb on Nagasaki, dropped three days later. Oppenheimer’s claim that Szilard’s petition would never reach President Truman also proved to be correct. However, paying attention to the moral dilemmas that arose among scientists at the time serves as a reminder that different outcomes were possible. The opera underscores the different models of action proposed by the various scientists of the project, some of whom understood their role as not only technical, but also political.

Further resources:

The opera on John Adams’ website: https://www.earbox.com/doctor-atomic/

A detailed synopsis of the opera: http://www.operainfo.org/broadcast/operaSynopsis.cgi?id=1000000000000130&language=1

Doctor Atomic’s libretto: https://www.opera-arias.com/adams/doctor-atomic/libretto/

Doctor Atomic: The Making of an American Opera, interviews conducted by Caroline Crawford and Jon Else, 2005–6 (Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2008): https://ohc-search.lib.berkeley.edu/catalog/MASTER_2417